When it comes to 3-point shooting, it’s better to be lucky than good

What's important in a team's shooting defense -- and what isn't?

We’ll begin the offseason with a few studies on the various inputs that go into every team’s game plan, and how statistics can help improve the way the game is played.

If you’re reading this, it’s likely you spend a great deal of time every year devising the best possible ways to create open shots for your team and the best possible ways to limit open shots for opposing teams. And that’s an important goal. But the numbers paint an interesting picture. They say it doesn’t matter as much as we think it does.

The stats say …

Shooting 3-pointers in basketball is an incredibly volatile skill — much more volatile than hitting the strike zone in baseball, completing a 10-yard out route in football or serving in tennis. And the college basketball season is relatively short, leading to high variability in teams’ shooting percentages.

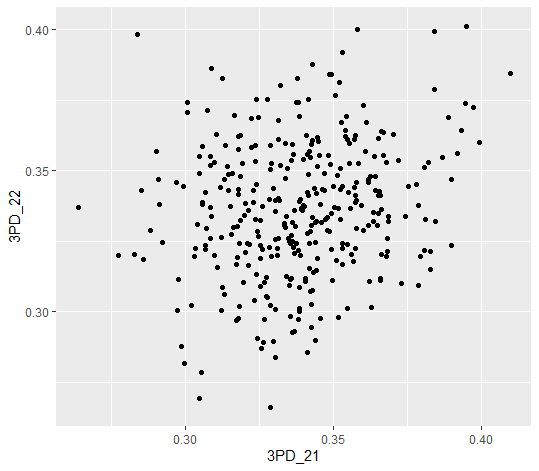

Our case goes like this: If 3-point defense is a reliable skill, then there should be a reasonably significant correlation in teams’ stats from one year to the next (given that most teams keep the same coaches and many of the same players from one year to the next). But there isn’t. Here’s a plot showing Division I teams’ opposing 3-point shooting percentage from 2020-21 on the horizontal axis and 2021-22 on the vertical axis.

The correlation between these two seasons is only 0.194, which is quite weak. The same correlation between 2019-20 and 2020-21 is 0.208. On the other hand, 2-point shooting defense is much more stable from one year to the next (more on that in a future edition of this newsletter).

Some of the changes can be explained by coaching transitions, strength of schedule and player attrition, especially in this era of college basketball. But much more of the variability comes from simple luck.

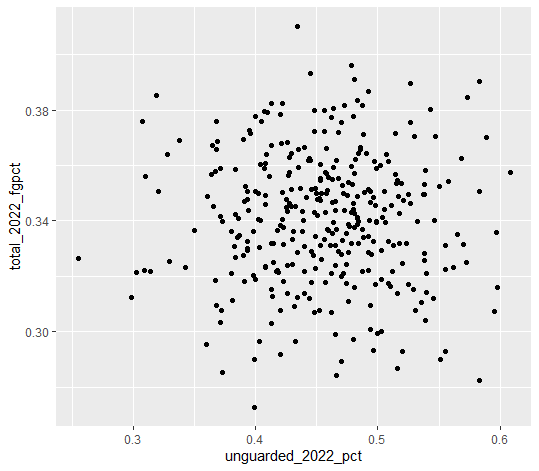

If contesting shots were the whole battle, then the percentage of shots that are guarded should be a significant determinant of the success rate. On a more granular level, we see that that’s not the case. On this plot, the X-axis shows the percentage of each team’s opposing shots that are labeled “unguarded,” according to Synergy, and the Y-axis shows the percentage of each team’s catch-and-shoot attempts that are successful. There’s almost no correlation:

To be clear, contesting shots is important — this past season, Division I teams made 36.9% of unguarded looks and only 31.7% of guarded looks. That 5.2% gap is about the same as the difference between the 48th-best 3-point shooting team in the country and the 296th-best 3-point shooting team in the country.

Some teams find some measure of consistency in perimeter defense. Houston, for instance, ranked 15th in 3-point defense in 2020-21 and eighth last season. But for every team like Houston, there’s a team like Colgate.

In the 2020-21 season, Colgate allowed opponents to make only 26.4 percent of their 3-point attempts, which was the best mark in the country that season and the lowest since 2005. They were a very similar team this past season: They returned four of five starters for 2021-22, and they finished with about the same record in league play (11-1 vs. 16-2). They again earned a No. 14 seed in the NCAA Tournament. But the Raiders of 2021-22 ranked 184th in the country in 3-point percentage defense, at 33.7%.

If you assumed that was because they were playing much worse perimeter defense, you’d be wrong. Colgate guarded 42.4% of catch-and-shoot attempts in 2020-21, and 43% this past season. The difference was that the Raiders’ opponents made only 17.9% of 112 guarded attempts in 2020-21, and 32.3% in 2021-22.

That made them a particularly lucky team in 2020-21; no other team saw its opponents make less than 20% of guarded catch-and-shoot tries. This season, the Raiders were a bit less fortunate than the average team.

Colgate played only 16 games in 2020-21, a particularly strange season because of the pandemic. So the full-season shooting statistics we have from 2021-22 are quite volatile. Any shooting statistics from a half-year or less — say, at the beginning of league play each year — should be even more so.

The other challenge in measuring 3-point shooting defense is that invariably, every team is going to guard some 3s and every team is going to leave some open. Remember that 5.2% difference between guarded and unguarded 3s? That’d be our expected difference between a team that leaves every 3 unguarded and a team that contests every 3.

But, of course, neither of those extremes is realistic.

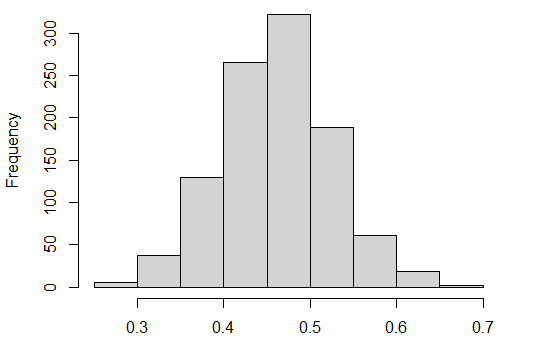

Over the past three seasons, the highest percentage of catch-and-shoot looks that teams have left unguarded is 67.9%. The lowest percentage is 25.5%. But contesting shots follows a normal distribution. The vast majority of teams (95%) fall in the range of 34% to 58%; finishing a season beyond either end of that spectrum is quite difficult.

What does this mean for us? Well, each of a team’s important characteristics factors into the game plan for the final minutes. If 3-point shooting defense is hard to pin down, then we shouldn’t let the opponent influence a team’s projected shooting percentage.

Indeed, 3-point shooting percentage is hard enough to capture without introducing the noise created by a specific opponent. That’s a subject for another newsletter. For now, we can say that if you’re down by 5 with 0:40 to play, whether you’re facing UC Irvine (first in opposing 3-point percentage, at 26.6%) or Chicago State (358th in opposing 3-point percentage, at 40.1%), you should feel free to let the 3-pointers fly.

For instance:

Houston 76, Wichita State 74 (2OT)

Situation: Houston 74, Wichita State 71, Wichita State ball, 0:13.0 left in 2OT, both teams in double-bonus.

Wichita State rec: Need 3

What happened: Wichita State’s Craig Porter Jr. isolated his defender (Jamal Shead), took a step-back 3 and drilled it to tie the game with 5.4 seconds to play.

Unfortunately for the Shockers, Houston managed to drive the length of the floor and capitalize on a defensive breakdown for a game-winning dunk with 1.2 seconds.

Why it matters: Some teams in Wichita State’s position would have balked at an important 3 against Houston in the closing seconds of the game. But GTD still would have recommended taking the 3, if possible, and the Shockers did so.

With only 13.0 seconds, Wichita State likely didn’t have time to get up and down the floor twice. The ball didn’t cross midcourt until about 0:10 and didn’t get to the 3-point line until about 0:08. If they were lucky, the Shockers would have scored 2 with about 0:04 or 0:05 and still had to foul Houston. Then, they would have been rushing down the court, at which point they very likely would have had to take a desperate 3 anyway.

The 3 they did take — with Porter at 0:07 — was not desperate. It was a great look, no matter what name was on the opponents’ jerseys. Credit goes to Wichita State for tying this game up. The fact that Houston scored in response took the shine off this decision a bit, but in the long run the Shockers put themselves in great position. Teams that have regained possession with 0:05 to play in a tied game have won on buzzer-beaters on only 28 of 110 chances (25.5%) over the past five seasons.